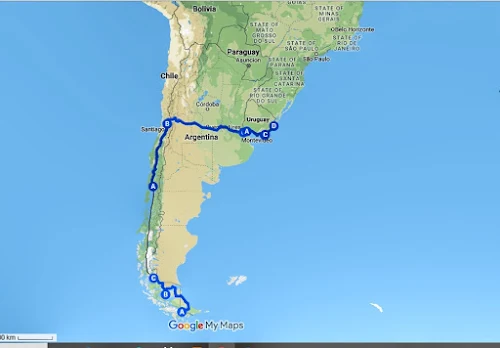

ARGENTINA & CHILE

2,950 Kilometres - 96 Days

24 November 2010 – 27

February 2011

PHOTOS - Chile

E-BOOK

35

PATAGONIA – (ARGENTINA & CHILE)

350

Kilometres - 37 Days

24

November 2010 – 31 December 2010

PATAGONIA

(ARGENTINA)

24

November - Cape Town, South Africa - Ushuaia, Argentina

I

immensely dislike flying with a bicycle and the trip to South America required

a five o’clock start to catch an early morning flight to Ushuaia via Buenos

Aires. The flight was rather long, being 9 hours and 20 minutes to Buenos Aires,

and a further 3 hours and 30 minutes to Ushuaia. On the positive side, all went

well except for having to pay the overweight baggage fee on the last leg.

A

taxi ride took me into town and to Hostel Haush, my home for the following three

nights. At last, I’d arrived at Isla Grande, Tierra Del Fuego, an island shared

with Chile and separated from the mainland by the Strait of Magellan. The

island formed the Americas’ southernmost tip, and from Ushuaia boats departed on

excursions to Antarctica.

Ushuaia

was picture pretty but understandably freezing. Fortunately, enough outdoor

stores were scattered about to stock up on warm clothes. With the sun setting

at 21h30, it felt odd going to bed when it was still light outside. By 23h00,

the time finally came to crawl in and be horizontal.

25

November – Ushuaia

Ushuaia

reminded me of Alaska’s brightly-painted, corrugated-iron roof homes and snowy

mountain backdrops. Situated on the Beagle Channel and at the foot of the Andes

Mountain Range, Ushuaia was commonly known as the most southern city in the

world. Although, with a population of a mere 64,000, Ushuaia wasn’t much of a

city. Its southern location at 54.8019° S meant artic weather year-round with a

high of barely nine degrees in the warmest months. Heating systems were thus on

year-long, including in summer!

Being

December and arriving from Australia via South Africa, I thought the conditions

particularly severe.

Having

only an inadequate pair of sandals, I made a beeline to shoe shops and spent a

small fortune on a pair of wonderfully comfortable light-weight Merrell hiking

shoes, hoping they would keep my feet warm.

The

rest of the day was spent frequenting the numerous shops and stocking up on everything

needed. The bike shop, Ushuaia Extremo, did an excellent job of reassembling the

bike.

26

November - Ushuaia – Tierra del Fuego National Park – 50 km

Dressed

in my warmest clothes (including my brand-new shoes) I biked into the National

Park. The park gate was 12 kilometres from the town centre and a leisurely ride

along a dirt road. Although bitterly cold and feeling I resembled an icicle, the

scenery was spectacular. The end of the park road indicated the end or start of

Route 3, also referred to as “The-end-of-the-world”. This might’ve been the end

of the road for many, but to me, the park marked the beginning of my route through

the Americas. After a short (and relatively quick) amble around the park, upon returning

tiny snowflakes fell from the sky. Regrettably, they melted instantly and I

can’t say I’d cycled in snow.

After

much deliberation, I purchased rain pants and a beanie to ward off the

anticipated cold weather. Both would prove well worth the expense in the months

to come.

27

November - Ushuaia – Tolhuim – 109 km

I

was cautiously excited, as this was the day I was to start my travels through

the Americas. The route headed uphill out of Ushuaia and over the mountains,

past numerous ski resorts, some even sporting chair lifts, not something I was

familiar with. The road was in good condition, somewhat narrow but sealed.

Motorists were kind and gave cyclists a wide berth and a friendly warning hoot.

After

about 50 kilometres, the route reached the top of Paso Garibaldi, featuring a

view over Lago Escondido and Lago Fagnano. Mountains provided shelter from the

wind and thus a false sense of security. The road sped downhill past Lago

Escondido and onto Tolhuim, situated on Lake Fagnano. Tolhuim was a strange

town and it was challenging to find accommodation or shops; maybe there weren’t

any. Eventually, I discovered a good enough spot to bed down.

28

November - Tolhuim – Rio Grande – 113 km

Waking

to loose, corrugated-iron roof sheets banging in the wind, one intuitively knew

the day would become a long, hard one into the wind. Heading out of Tolhuim, swirling

dust clouds made it a desolate and lonely scene. The route led north to Rio

Grande, straight into the infamous Patagonian wind. In the cold weather and

while rain pelted down, driven by a near gale-force wind, the rain hit my hands

with such force that I wished for thicker gloves. Even though dressed in all the

warm clothes I possessed, I was freezing.

As

if the weather weren’t challenging enough, the rear gear cable gave problems,

but there was nothing one could do but battle on and work with the three remaining

gears. It didn’t make much difference, as I could barely average 10 km/h. The

wind grew stronger as the day wore on, slowing the pace to a mere five km/hr.

Still, I battled on, past vast windswept and barren-looking estancias. Goals

became shorter and shorter. Four times five kilometres sounded far more doable

than 20 kilometres at that stage. Every five kilometres, I rewarded myself by

eating a sweet or biscuit. Then, head down, I headed off into the howling wind.

Midday,

a stormwater pipe running underneath the road gave shelter from the wind, if

only to give the mind a break. It’s incredible what all runs through a person’s

head sitting alone in a stormwater pipe. This was indeed a mental game and,

back on the bike, it took fighting the wind with each turn of the pedal.

Barely

20 kilometres from Rio Grande, a kind Argentinean stopped and offered me a ride.

Smelling victory over the day I declined his offer. Seeing him disappearing in

the distance, I could’ve kicked myself wondering what was wrong with me. Instead,

gripping the handlebars, I pushed down hard on the pedals.

Eventually,

Rio Grande rolled into view. Exhausted, I crawled into Rio Grande, booked into

the first available guesthouse and fell asleep exhausted but pleased to have survived

such a harsh day.

29-30

November - Rio Grande

There’s

nothing better than waking up to the smell of coffee and toast, and I eagerly

crawled out of bed. An excellent breakfast was included in the room price (in

Argentina, a typical breakfast usually consisted of coffee and croissants, or

other pastries). At least the weather cleared, but the relentless wind didn’t abate

– maybe it never does. Nothing could prepare you for what is in store,

regardless of what you read or hear about the wind. If it weren’t that Ernest

and I’d battled into storm-strength wind day upon day along the Red Sea Coast

of Egypt, I wouldn’t have believed such a wind possible.

I

could feel a bout of laryngitis coming on (maybe from breathing all the icy

air) and was pleased for a day of rest. Priority was finding a bike shop to replace

the gear cables. The friendly chap at the bike shop advised fitting off-road

tyres for the dirt road ahead. Unfortunately, he could only get the tyres the

following day. Leaving the bike at the shop was no problem as the wind speed

was between 65 and 100 kilometres per hour. (I kid you not!)

1

December - Rio Grande – 19 km

Once

the bike was fixed, I was ready to roll. Regrettably, the wind won the day. After

battling 10 kilometres out of town, I eventually gave up and returned to Rio

Grande. Cycling wasn’t simply hard but also too dangerous and scary as the wind

blew me like a rag across the highway.

Hostel

Argentino was slightly less expensive than where I’d stayed before and made an

excellent place to wait out the weather. Three more cyclists were heading in

the same direction and waiting for a break in the weather. Watching the weather

forecast, there appeared no hope of the wind subsiding. We, thus, had no other choice

but to wait. In the meantime, some fine red wine was enjoyed and war stories

swapped, which became more impressive as more wine was consumed.

2

December - Rio Grande – San Sebastian (and by car to Punta Arenas) – 38 km

The

following morning, the wind looked deceivably less fierce than the previous

day. However, after hurriedly loading up and biking out of town, I found the

wind no less violent than the day before. Battered by wind kilometre upon

kilometre, each turn of the pedal became an achievement. The wind blew in random

gusts and every so often blew me off the road and into the barren no-mans-land.

I stopped counting the times I picked myself up to try again. Worse was that it

blew me into the road. Even though drivers were extremely courteous, cycling remained

nerve-racking. If the wind wasn’t enough, the weather was freezing and, at one

point, it started hailing. Wondering if things could get any worse, the wind

gathered strength, making it near impossible to ride. All one could do was hold

on to the bike, hoping not to get blown over. God knows I must’ve made a pathetic

sight as a kind truck driver stopped and offered me a ride to San Sebastian, almost

40 kilometres away. The truck’s safety gave false security, (or pure stupidity)

and once in San Sabastian, I got back on the bike.

The

border crossing between Argentina and Chile was barely 10 kilometres away and a

low-key operation. Nevertheless, the immigration office made a sad and lonely

sight: a small, unimpressive building in a vast windswept wilderness. There was

nothing around but barren land as far as the eye could see. The immigration

office further marked the end of the paved road, adding to the region’s desolate

appearance. From there on, a dirt track ran 140 kilometres to Porvenir, from

where ferries departed to Punta Arenas. Still, it took a while before all was

checked and cleared.

From

the immigration office, the route headed straight into the wind. Walking the

bike in the high wind along that desolate and windswept stretch of road, I felt

awfully lonely and sorry for myself.

Even

pushing the bike, I was blown over and fell into a ditch. Lying in the ditch, I

looked up into the face of a llama. It appeared even the llama was surprised to

see me. I got up, dusted myself off, waved the llama goodbye and tried again. There

remained 140 kilometres to the next town, and it was time to take stock of my

dire situation. Sitting by the side of the road I had no idea how to get myself

to Porvenir. The water I had was only enough to last a day. The wind blew with

such force one couldn’t even get on the bike, let alone cycle, and I was blown

over before both feet were on the pedals.

When

a helpful Chilean driver stopped to offer me a ride to Punta Arenas, reality

set in, and I realised hard-headedness wouldn’t get me anywhere. I tried but couldn’t

see any other option but to accept his offer. The Patagonians were incredibly hospitable.

3-4

December - Punta Arenas

Once

in Punta Arenas, Hospedaje Independencia offered both camping and dorms. Being the

cheapest accommodation in town, backpackers from all over the world packed the

place. Much of the region once belonged to Jose Menendez, wool baron of his

time. Even today, the area is still sheep country, and wool and mutton remain

the region’s primary income.

Francois

(a cyclist from Hostel Argentino in Rio Grande) arrived by bus, and it felt like

meeting an old friend. Unfortunately, the weather station alerted high winds

(according to them, gusts of over 100/120 kph were possible). Therefore, staying

put and rechecking the weather the following day was best. By evening, all

huddled inside the hostel kitchen, where the owner made Pisco Sour drinks for

everyone. By the end of the evening, it didn’t feel that cold stumbling out to the

tent.

5

December - Punta Arenas – Puerto Natales – 21 km

The

weather looked much improved, and after a leisurely start, I biked out of Punta

Arenas. Still, the wind barely allowed clearing the city limits (roughly 10 kilometres)

and then hit with full force. I genuinely felt defeated and didn’t know how others

cycled in this wind (I subsequently found most waited it out). Riding was too scary

as the wind wasn’t directly from the front, but generally from the side. Furthermore,

it came in gusts, blowing one off the road or into the traffic. It was better

to admit defeat and return to town, after which I flew downwind into the city

centre.

From

Punta Arenas, a bus ride took me to Puerto Natales. Arrangements were made with

Yuta and Francois to do a trek once in Puerto Natales. However, even the bus appeared

to have difficulty staying on the road. What an unforgiving area Patagonia was.

The plains were barren, treeless and windswept. Now and then, a lonely and

forlorn-looking estancia appeared, some even deserted.

Once

in Puerto Natales, Josmar Hostel offered dorms and a well-protected campground,

making it a perfect place to arrange treks.

6

December - Puerto Natales

Francois

and Yutta arrived, and the day flew by as preparations took place for our eight-day

Torres Del Paine trek. Hiking shops rented bags and walking sticks, and we stocked

up on food. The backpacks were heavy, and I wondered if it would even be

possible to make the first few kilometres (and that was before packing the

wine). Basic stuff like a tent, sleeping bag, an eight-day food supply and warm

clothes were already a massive amount of gear.

7

December - Torres Del Paine - Las Torres – Campamento Seron

Torres

Del Paine National Park was exceptionally well organised. A 7h30 bus ran to the

park and a small minibus to Hotel Las Torres, where the first day’s hike started.

Then, heaving the heavy packs, we strolled off to our first campsite.

Our

route came with lovely views of snowy mountains and lakes. Unfortunately, our

first campsite was exposed to the elements, and the wind blew as it could only

blow in Patagonia. Somehow, we managed to cook but I was sure the tents would take

off during the night.

8

December - Torres Del Paine - Campamento Seron – Refugio Dickson

My

ankles were reasonably sore upon waking, but I paid no attention to it as minor

aches and pains usually came with the territory. In addition, I’d spent the best

of the previous four years on a bicycle and hardly ever placed any weight on my

feet and ankles. Thus, I could expect them to be slightly tender.

After

a leisurely start, a short stroll took us to our second campsite. Again, the

day turned out to be enjoyable and relaxed – it was a good thing, too, as it

started raining, a drizzle which continued for the rest of the day. On reaching

Refugio Dickson, we were wet and cold, my ankles throbbed, and walking became challenging.

Dickson was, however, one of the best camping areas on the trek. It had a

lovely refugio with a fireplace and a communal sitting area, where coffee, tea,

and a few basic meals were for sale. Inside, the refugio was social, with many wet

and cold bodies (and boots) huddled around a small fireplace. When it came to

wet boots and cold feet, hiking was the same worldwide.

Outside

the weather was bitterly cold and nowhere inside seemed warm enough, even though

I was dressed in all I had. Soon, it started snowing and the entire landscape turned

a brilliant white. The falling snow was quite a novelty initially but wasn’t as

romantic as imagined. Fearing the poor tent would collapse under all the weight,

I scraped off as much as possible.

9

December - Torres Del Paine - Refugio Dickson – Campamento Los Perros

The

trek to Refugio Dickson was another short walk, and there was no need in

rushing to pack up. Also, rumour had it that temperatures were even lower at

Dickson, and we only got underway at around 12h00.

Although

trying to ignore the pain by taking anti-inflammatories, walking became a

serious struggle. The hike nonetheless offered stunning views of glaciers and

surrounding mountains. My pace slowed, and François accompanied me as I crawled

along at a snail’s pace. Finally, I dragged myself to camp aided by my two

walking poles. It’s a terrible feeling knowing you’re holding up your fellow

hikers, but there wasn’t anything I could do. On arrival at camp, the cold

weather made it essential to get the tent pitched as soon as possible, as I

knew there would be no getting up once inside.

People

were incredibly kind and helpful, all offering painkillers and lotions.

However, I knew I could not cross the pass in the morning. The pass was a steep

climb of almost 1,000 metres in deep snow and it was at least a six-hour walk

to the next camp.

10

December - Torres Del Paine - Campamento Los Perros

I

was stuck in the tent and couldn’t move. My ankles and feet were too painful to

place weight on them, and the slightest bit of pressure sent shock waves of

pain through me. I waved Francois and Yutta goodbye and then had to think about

how to get myself out of there. My lack of the Spanish language made arranging

anything complicated. Eventually, information from Los Perros’ people was that one

could organise a horse but not from Los Perros. It would take returning to Dickson

and maybe once there staff could arrange a horse. I didn’t know how to achieve

that, as even standing was impossible.

Later

that day, a group of British horse riders arrived, and it was good to hear a

language I understood. Their guide came to my tent and offered to take my

backpack to Dickson if I could make it there on foot. I was incredibly grateful

for this immensely generous offer and decided, come hell or high water, I would

get myself to Dickson.

11

December - Torres Del Paine - Campamento Los Perros – Refugio

Two

of the horse riders were South African doctors working in London. True to

nature, they had a fair amount of medicine and offered painkillers. Thanks to

them, I could just about get out of the tent and stand on my feet.

Once

the tablets kicked in, and aided by my walking poles, the slow shuffle along

the path began. This wasn’t merely embarrassing but incredibly painful. I kept

telling myself, “It’s only pain” and my usual motto of “Even this will pass”,

but these were empty words. The pace was slow, one step at a time; not even the

painkillers seemed to help after taking almost all of them. It’s amazing what

one can do when there’s no other option. Finally, I stuck the walking poles

into the ground and dragged myself forward; a slow, painful and tedious task.

On

shuffling into Dickson, I was immensely proud of myself. It was a task which

seemed impossible just a few hours before. In Dickson, three other trekkers

were waiting for horses. Like the previous night, I thought it essential to

pitch the tent and do all the necessary tasks, like filling up with water,

getting food and going to the toilet. Once inside, there would be no getting up.

Even aided by the walking sticks, it was barely possible to keep moving until all

was done. Exhausted, I flopped into the tent.

Soon,

a fierce wind picked up and securing all tent ropes and pegs became crucial. Crawling

on all fours, I hammered in pegs and tightened strings. What a sight I must’ve

been! Still unsure if the tent would hold up in such a strong wind, I supported

it by leaning against the windy side. It blew so strong it became barely possible

to hold it up, even leaning against the side with all my weight.

12

December - Torres Del Paine - The “rescue.”

Early

morning, and quite unexpectedly, a message came that a horse had been arranged.

The only snag was that the horse was on the river’s opposite side. Even swallowing

the last four painkillers, it felt the tablets had no impact. And to think, I

always considered myself one with a high pain tolerance! Nevertheless, I got

the tent down through sheer determination and packed the backpack in the high

wind. Eventually, the camp owner came to help, and I limped off towards the

river.

Driven

by high wind, the river was a torrent and boatmen found it impossible to hook the

boat onto the overhead cable, a permanent installation across the river. By

then, both ranger and horse were waiting on the opposite side. Eventually, all

gave up and returned to the refugio. Following a hearty lunch, the men returned

to the river to check the conditions.

Eventually,

the boat got hooked onto the cable, and with my backpack on the boat, we made

it across by pulling the boat along the wire. Getting out of the boat, across

rocks, and onto the opposite bank was a slow and painful task, and I surmised

quite a spectacle but I had no ego left by then.

Eventually,

I met the very patient ranger and horse - I later discovered he was the most

experienced and longest-serving ranger in the park. Once heaved onto the horse

by strong hands, we galloped off following a horse trail, through an exceptionally

isolated part of the park. Nearly two hours later, we reached a dirt track

where an off-road vehicle awaited us. I had no idea it would be such a mission.

With

a skilful driver, we continued a fascinating ride through the park. A jeep

track went up over mountains, through rivers and marshlands and past some of

the most stunning vistas the park could offer. What an adventure, albeit a tad

uncalled for.

An

ambulance waited at the park’s main gate and, embarrassingly, I was loaded in

and taken to Puerto Natales Hospital. The fact that I’d been hiking and

sleeping in the same clothes the past five days and that each person wanted to look

closer at my feet, which had been in the same shoes and socks for the same

amount of days, was part of my embarrassment.

At

the hospital, x-rays were taken, my feet were examined, and I was declared

healthy apart from pulled ligaments and severe tendonitis. Though the doctor

indicated my injuries would take four weeks to heal, I paid little attention and

was sure I would be up and running within a day or two. Then, of course, I had the

luxury of an intravenous painkiller. Still, it never had the slightest impact.

There was no hopping and skipping out of the hospital, as anticipated.

The

time was 11 p.m. before hailing a taxi to take me the short distance to the

hostel. Then, finally, I could rest my weary feet. The total cost of rescue and

hospital came to US$470. A reasonable amount, considering what was required,

and how many people were involved in getting me out. I can only thank the

helpful and professional staff of Torres Del Paine National Park.

13-25

December - Puerto Natales

All

wasn’t well yet and, luckily, the staff at the hostel offered to get the much-needed

anti-inflammatories from the pharmacy. At last, I could shuffle to the bathroom

for a much-needed shower. Thank goodness for the laptop, which kept me occupied.

All in all, it was my fault for thinking I could do more than my body could. Following

nearly four years of cycling, my ankles were weak from a lack of walking and it

was a reminder that I should live a more balanced life.

Yuta

and François returned from their hike and they had a wonderful time. Needless to

say, I was green with envy.

I

waited and waited but healing was an excruciatingly slow process. At least anti-inflammatories

and painkillers allowed for a slow shuffle to banks and shops. Day upon day, I

waited, but progress seemed dreadfully slow. The daily shuffle to the

supermarket was a painful exercise at a snail’s pace. Finally, my friends moved

on. Still, I waited and thought it unbelievable that a common ankle injury

could take that long to heal. I was fed up and desperately wanted to get on the

road. Then, I received the sad news that severe tendonitis could take three to

six weeks to heal. This wasn’t what I wanted to hear. There are, sadly, certain

things in life one can do little about. This was one of those situations, and I

had no option but to wait.

I

woke with great anticipation each morning, only to find minimal improvement. Close

to despair and bored stiff, cycling into the wind didn’t sound all bad.

The

hostel was a favourite among young Israeli travellers, and they visited in

their hordes. They seemed to favour South America as a travel destination and

moved in packs. Seldom, if ever, did you meet an Israeli travelling solo.

And

I waited, and waited and waited!

26

December - Puerto Natales

At

last, it felt like my injuries were on the mend and walking was less painful than

before.

That

very evening, Ernest arrived from the north en route to Ushuaia. He looked

haggard from weeks of battling the wind (at least he had the wind from behind).

Harsh conditions along the Carretera Austral in Chile and the infamous Route 40

in Argentina could wear any traveller down. With much catching up to do since we

parted in Melbourne two months earlier, the chatter continued until late.

27

December - Puerto Natales

The

following morning, I sought out the ticket office to get information on the

Navimag Ferry which sailed between Puerto Natales and Puerto Montt – said to be

a spectacular three-day voyage via the Chilean fjords. I learned the weekly

ferry sailed that evening and had a cabin available. So, a quick decision was

made to take the boat, a trip I had been dreaming about for years.

Ernest

decided to throw a U-turn instead of proceeding further south. Even though the

passage was costly, it included four nights, three full sailing days, and

meals. Also, it would allow my ankles three more days to heal, but, most of

all, it would get me out of the fierce Patagonian wind and cold conditions, or

so I hoped.

The

odd thing was that boarding time was at 21h00, but the boat only sailed at 4h00

the following day. So, excited as a child to finally be on the move, I biked to

the harbour. Shortly past 21h00, we settled into our cabin on the Navimag ship,

Evangelistos. Although our cabin had four berths, we

were the sole occupants.

28

December - Puerto Natales – Puerto Montt - Day 1

Early

morning our ship sailed, and by 6 a.m., the boat was manoeuvring through narrow

passages and fjords. Snow-covered, jagged peaks surrounded us and a fierce wind

whistled by, and I was happy to watch the spectacle through my cabin porthole.

By

afternoon, the Evangelistos sailed past the vast and spectacular Glacier Amalia

and I ventured outside to snap a few pictures, albeit it being bitterly cold.

The scenery was impressive with thousands of uninhabited islands, snowy

mountain peaks and icy-looking glaciers in the distance.

We

had already had two excellent meals during the day, and at supper discovered one

could request a vegetarian main course. I was served a delicious vegetable stew

and rice with a small side salad.

29

December - Puerto Natales – Puerto Montt - Day 2

Like

the previous day, breakfast consisted of bread, porridge/eggs, cheese, ham,

fruit, yoghurt, cereal, juice, and coffee. All meals on board were excellent,

and there were more than enough.

The

captain pointed out a shrine on a small island, said to be the Guiding Spirit

of all sailors, and a shipwreck known as an insurance scam before heading out

of the channels into the rolling swells of the Pacific Ocean. When we cleared

the fjords’ protected waters, the ship began to roll wildly and it was best to

stay in one’s cabin.

Dinner

was excellent, as usual, but there were (understandably) far fewer passengers

in the dining hall, and it was somewhat tricky to balance one’s food tray on

the way to the table.

30

December - Puerto Natales – Puerto Montt - Day 3

As

before, breakfast was enjoyable, though some passengers still seemed a little

green around the gills. By midday, the Evangelistos was back in the calm waters

of channels and sailed, yet again, smoothly without us having to cling to every

conceivable stationery item.

The

early morning fog burned off and brought excellent vistas of the Southern Andes

Mountains with their jagged peaks and snowy volcanoes. The day further turned

out our first day of calm sailing and sun simultaneously. The outside upper

deck with bar/lounge was popular; by afternoon, some paler passengers resembled

well-cooked crayfish.

As

before, we stuffed ourselves at dinner time and, as any good ship would have it,

our final night came with a party.

31

December - Puerto Montt

Our

ferry docked at Puerto Montt during the wee hours of the morning, and practically

all trucks had already departed the cargo decks upon waking up. After breakfast,

the time came to disembark and continue with our regular lives.

A

short ride took us into the city centre and to the hospedaje where Ernest

previously stayed on his way south. In typical Chilean style, the building was

a rickety, three-level, shingle-clad home with lace curtains and wooden display

cabinets, housing all kinds of family heirlooms. It felt I had finally arrived

in Chile proper. The elderly owner was quite interesting and had owned the home

– named merely B&B – for 40 years.

Although

New Year’s Eve, our search for excitement revealed little. In general,

restaurants and bars were closed, and Chileans appeared to celebrate at home. There

were, however, spectacular midnight fireworks at the pier. Our host invited us

for a drink with his family and friends, who were busy welcoming the new year.

36 CHILE

1305

Kilometres - 27 Days

1

January – 27 January 2011

1–2

January - Puerto Montt

Waiting

to be 100% confident on my feet, two more days were spent in pretty Puerto

Montt. I lay watching TV while Ernest polished off two bottles of whiskey and a

case of beer. I realised nothing had changed and wondered how long it would

take me to face reality!

Puerto

Montt’s weather was relatively mild, and I was happy to be out of Patagonia.

Unfortunately, Patagonia wasn’t as picturesque as predicted. All I remember was

a ferocious wind and a hike that went very wrong.

By

afternoon, a reasonably strong earthquake hit Chile. Mercifully, it occurred

pretty far north, and only a moderate tremble was felt in Puerto Montt. Our

rickety guesthouse swayed from side to side, but luckily no damage was done.

Surprisingly, no one seemed perturbed about it.

3

January - Puerto Montt – Puerto Varas – 20 km

The

short ride to picturesque Puerto Varas was my first cycle in a long while.

Founded by German settlers and still known as a place with strong German

traditions, Puerto Varas was picture-postcard pretty. The area was highly

touristy due to its location on the shore of Llanquihue Lake, its unmistakably

Germanic architecture, pretty residential neighbourhoods, and well-tended

gardens.

Scenic

places are bound to have hordes of backpackers, fancy hotels and pricey

restaurants. Regrettably, the weather was overcast and drizzling. Thus, there

was no glimpse of the famed Osorno volcano or the snow-capped peaks of Mt

Calbuco and Mt Tronador from across the lake.

I

was happy my ankles held out and felt more confident to continue my travels.

Walking caused some discomfort, but it gave no problems biking.

4

January - Puerto Varas – Frutillar – 43 km

Frutillar

was the next settlement on the lake and one more town founded by German

settlers in 1852/6. During this time, countless German settlers arrived under

the official colonisation programme of Southern Chile.

Frutillar

had no camping on the shores of the lake, but we found a lovely spot in

someone’s garden under a large cherry tree. I was happy the second day of

cycling went well without any aches or pains.

5

January - Frutillar – Osorno – 70 km

One

couldn’t wish for a better start to a recovery ride. Route 5, or the

Pan-American Highway, was in excellent condition with a broad shoulder. A

tailwind, as well as beautiful sunny weather, made it effortless riding.

It

was the first time it became possible to cycle in short sleeves in quite a

while. I was even more delighted to find lodging in the centre of Osorno. The

place had an excellent ground-floor room, with a door leading to a garden, TV

and hot shower. Osorno wasn’t on many travellers’ lists, but it made a perfect

overnight stop on the way north. A walk around town revealed typical wooden

houses, an imposing cathedral, and a fort.

6

January - Osorno – Los Lagos – 95 km

Route

5 was Chile’s longest road and ran 3,364 kilometres from Peru in the north to

Puerto Montt in the south and formed part of the Pan-American Highway. We

followed this road north, and another perfect day was spent riding Chile’s lake

district. The weather was warm, with a slight tailwind, and our path ran past

forested areas with the Andes mountains as a backdrop.

A

short detour led to the small and un-touristy village of Los Lagos. Situated on

the Calle-Calle River, it consisted of a quaint community with ramshackle accommodation

in the town centre. I loved these small villages with their central plazas busy

with people and bounded by streets dotted with municipal buildings, churches,

and a few shops.

7

January – Los Lagos – Loncoche – 84 km

Once

across the Rio San Pedro, Route 5 continued north through a eucalyptus forest.

A mild tailwind made it comfortable and enjoyable cycling. The weather was

warm, and the way gently undulating, past densely forested areas and vistas of

snow-capped volcanos. Needless to say, I was thrilled to be out riding.

Roadside cheese stalls made for convenient shopping, and the rest of the way

was spent dreaming up ways of enjoying it.

Eighty-four

kilometres further was the tiny hamlet of Loncoche which boasted excellent

lodgings in the town centre (outside and ground floor). Loncoche was a typical

small Chilean town with a plaza surrounded by municipal buildings and a church.

Ernest

returned from the supermarket with a bag of salad ingredients and proceeded to

make a noodle salad, adding heaps of cheese.

8-9

January - Loncoche – Temuco – 88 km

Clear

skies, sunshine and the lack of a headwind made it a perfect day for bicycle

touring. I wore a big grin as I knew my luck had to change sometime. Following a

leisurely 88 kilometres, the town of Temuco came into view. It took a tad

longer than usual to find outside ground-floor space, preferred to being cooped

up on the third floor with no external windows.

Temuco

was a pleasant city with a leafy square, making staying the following day an

easy choice. A non-cycling day usually came with the regular chores of laundry

and the Internet. The municipal market sold typical Chilean cheese, fruit, fish

and meat. Horse butcheries, something foreign to me, were plentiful.

10

January - Temuco – Collipulli – 102 km

Albeit

a mild headwind in the afternoon, the day remained a super day of biking. The

cold south had softened us up, and loads of sunscreen were required. However,

being in warm weather without a howling wind was indeed a pleasure.

The

small town of Collipulli was up next and came with the historical Malleco

Viaduct, today a national monument. The bridge consisted of a railway bridge

built in 1890, the highest such bridge in the world. I loved these little

villages where people went about their lives without the tourist influence.

Collipulli had a central park/plaza, colourful wooden houses, a market, a church,

and a town hall. A guesthouse in the centre made it an excellent place to chill

out after a day on the bike.

11

January - Collipulli – Los Angeles – 77 km

Blue

skies abounded and the sun was out, making biking the Pan Americana Highway (Route

5) a delight. The route to Los Angeles ran through a wooded area with

substantial rivers and a few camping areas.

As

the previous days, we encountered plenty of roadside food stalls, frequented

mainly by truck drivers. Closer to Los Angeles, the countryside became more

rural with vast farmlands. Not to be confused with Los Angeles in the USA, this

was an agricultural town with the highest rural population of any Chilean

municipality.

Los

Angeles was close to the Laguna del Laja National Park and, consequently, a

jumping board for those wishing to visit the park. The previous year’s

earthquake hit the region hard, and the town was still recovering. Rebuilding

was in progress, but sadly several buildings were still in ruins. Our abode

came with a TV and a BBC news channel and it seemed not an awful lot was

missed. It was amusing to see what the BBC considered world news.

12-13

January - Los Angeles - Chillan – 113 km

After

making a few sandwiches, the time was eleven o’clock - nothing unusual in

Chile. People went to bed late and only got going at around 10 a.m. Ernest

spotted a welding shop and had his bike’s front rack repaired - it broke on the

gravel roads along the infamous Route 40 when he was blown off his bicycle.

Our

route ran north past densely wooded areas, waterfalls, and viewpoints. Chillan

was another town in a rich agricultural region, on a vast plain, between the

Andes mountains and the coast. The town sported an old city with cobblestone

lanes and is said to be Bernardo O’Higgins’s birthplace. O’Higgins, regarded as

Chile’s liberator, was the driving force behind Chile’s independence from

Spain.

Chillan

had a relaxing vibe with numerous squares and parks; in fact, it was so

tranquil, we stayed for two days. The town had a beautiful town centre with a

mall, charming street-side cafes, and a sizeable open-air street market.

With

Chillan situated in a seismic activity region, it has suffered devastating

earthquakes throughout its history. Earthquakes partially destroyed the town in

1742 as well as in 1928. Chillan further sat near the epicentre of the 2010

earthquake (magnitude 8.8), which again caused severe damage. During our visit

in 2011, the destruction was clearly visible, and our abode was slanting to

such a degree that one could easily roll out the door.

14

January - Chillan - Linares – 109 km

Signboards

indicated 400 kilometres to Santiago and that we found ourselves in Central

Chile. It indeed looked like such while biking past large farming areas on

central Chile’s fertile plains.

After

turning off to Linares, a cycle path lead into town. I was surprised by the

number of historical buildings; unfortunately, the majority were still

off-limits due to the 2010 earthquake. However, close to the town square was

the Cathedral Church of San Ambrosio de Linares, one of the most beautiful

buildings in town. This was indeed a Roman Catholic country. Again, I spotted a

surprising number of cathedrals for such a small village.

After

locating an affordable establishment with cable TV (for Ernest) and storage for

the bikes, Ernest, as usual, lit his petrol stove and cooked pasta. The cooking

process took place in the bathroom; not very hygienic, but delicious,

nevertheless.

15

January - Linares - Talca – 56 km

The

day came with a slight headwind which hampered our efforts. After 56 kilometres

and feeling lethargic, Talca, situated in the Maule region, the largest

wine-growing region in Chile, made a perfect overnight stop—it was time to

taste their wine.

Talca

wasn’t only home to several wineries, but also a university, which sounded

pretty good to me. Regrettably, Talca was another place severely damaged by the

February 2010 earthquake. All budget digs in the older part of town had been

destroyed, and empty lots remained where those hostels once stood. It was quite

shocking to see such devastation.

For

the past three days, our overnight lodging was in towns affected by the

previous year’s earthquake - Chillan, Linares and Talca. Even at the recently

re-opened hotels, the open doors didn’t close, and the closed doors couldn’t be

opened. Seeing the collapsed buildings and empty plots remained a sad sight.

There

wasn’t much to do in Talco but walk to the Santa Isabel supermarket (in all

towns) to get supplies to make supper. I guessed earthquakes weren’t new to

that area as I learned the name Talca means thunder or a volcanic eruption in

the Mapuche language.

16

January - Talca - Curico – 73 km

On

departing Talco, a good tailwind assisted us to Curico. The day looked

promising until a loud bang brought us to a sudden halt. Thank goodness, it was

merely Ernest’s tyre that had a blowout but I almost hit the deck and started

leopard crawling (I’m South African, after all).

The

rest of the day was enjoyable riding through a wine region, and the farms

passed very much resembled those at home in the Western Cape. On reaching

Curico, the pleasant Hotel Prat lured us in. The place was rather convenient

with its guest kitchen and outside ground-floor quarters.

As

with the other towns in the area, Curico was destroyed by an earthquake in 1928

and severely damaged by the previous year’s quake. Fortunately, the Plaza de

Armas (the main square) remained intact and the most frequented place due to

its trees and pretty historic bandstand.

Curico

is situated 46° north. The sun sets after 9 p.m. and it darkens around 10 p.m.,

making for long summer days. I, therefore, understood their need to have long

siestas, as virtually all shops were closed between 12 and 4 p.m.

17

January - Curico - Rancangua – 112 km

Heading

to Rancangua was a pleasant day of biking. Vineyards stretched as far as the

eye could see, with the ever-present Andes to the east. Following a few cold-drink

stops, we slinked into Rancagua. I didn’t expect much of the town but was

pleasantly surprised.

Rancagua

had a historical section with an ensemble of old buildings. The town was a fair

size with a pleasant central square known as Plaza of the Heroes where the

Battle of Rancagua occurred. It is referred to as the Disaster of Rancagua, as O’Higgins

and his army had to beat a hasty retreat here and hide in nearby caves while

fighting for independence.

18-23

January - Rancagua - Santiago – 92 km

Santiago

(population around six million) was one of the most convenient capital cities

to pedal into. Next to the highway, a service road led straight into the city

centre. Ernest knew precisely where to go, as he flew into Santiago from

Australia a few months prior. All this made riding to Hostel Chile Inn

comfortable - where Ernest stayed before heading south.

Barrio

Brazil, a district close to the city centre and within comfortable walking

distance of almost everything, housed a few hostels. The underground metro

railway station was barely 100 metres from the door and made for easy

exploring. The metro could take you practically anywhere in the city and was reasonably

inexpensively.

Our

hostel was one of the many old three-storey buildings in the area. Nearly all of

these buildings came with soaring ceilings and huge rooms. I understood these

were former grand homes, generally with upper decks and ground-floor

courtyards. The staff at the hostel was super hospitable and invited all to a

free barbeque on the deck. We danced the Macarena till the wee morning hours

with the staff and a broad mixture of guests (Italians, Germans, Brazilians,

Venezuelans, Mexicans, and Chileans).

The

subsequent days were spent wandering around town, enjoying the novelty of

taking the underground and the funicular up the San Cristobal hill. Besides a

statue of the Virgin Mary, the viewpoint offered panoramic vistas of the surrounding

areas.

My

laptop gave me endless trouble, and I handed it in to be repaired, but on

receiving it found it still faulty. I took the computer to a more reliable

store and was told it would only be ready on the Monday. Upon receiving it, I

found it only spoke Spanish. After rushed last-minute shopping, we were all set

for our final stretch in Chile before heading over the Andes to Argentina.

25

January - Santiago - Los Andes – 81 km (+3km through the tunnel)

After

an entire week in Santiago, Ernest and I, finally, resumed our journey. Soon

after leaving, the landscape changed abruptly. Gone were the wooded areas and I

was surprised to find myself in a desert-like landscape.

The

route north to Los Andes was via a reasonably steep climb over the mountain in

sweltering weather. Fifty-five kilometres after biking out of Santiago, a

tunnel prevented cyclists from proceeding any further. Tunnel staff quickly

spotted us, came to the rescue with a truck and dropped us on the opposite

side. A pleasant descent led to the Los Andes Valley, where a small roadside

establishment with a beautiful lawn got our attention. Seeing they had a

campground out back and sold homemade bread made staying a no-brainer.

26

January - Los Andes - Roadside camping – 50 km

The

following morning our path headed mostly uphill. As expected, our pace slowed

considerably, as we stopped numerous times to snap a few pics and fill our

water bottles. By the end of the day, camping was on a hill above an emergency

truck stop with excellent views of the surrounding mountains.

The

adjacent cascading stream from the snowy mountains provided fresh water. Even

without a single alcoholic drink, Ernest washed in the river’s icy waters. It

was still early and a relaxing afternoon was spent enjoying the sunshine. That

evening, while having supper, a jackal came trotting past. Soon it became pitch

dark and a zillion stars lit the sky—truly magical moments.

27

January - Roadside camp, Chile - Puente Del Inca, Argentina – 40 km

This

was the day the route headed over the Andes to Argentina. The road zig-zagged

up the pass and, though the gradient was acceptable, it remained a steep and

dreadfully slow 22-kilometre climb from where we had spent the night. Roadworks

caused lengthy delays and provided a much-needed time to take a breather.

Finally, after huffing and puffing to the top, one could look down at the

winding road coming up the mountain and I could hardly believe I had made it up

the pass. After reaching the top and yet another ride by the authorities

through a tunnel, 18 kilometres remained to the customs office.

The

border crossing was uneventful, and immigration staff simultaneously stamped

people out of Chile and into Argentina. From the immigration office, the path

descended past the small settlement of Las Cuevas with no more than a few

timber restaurants and a strong smell of lentil soup. Upon crossing the border,

Ernest and I reached the end of Patagonia and Chile. After my disastrous start

in the Americas, Chile was a welcome change and a relaxing and rewarding ride.

To this day, I claim Patagonia will never see me again. LOL.