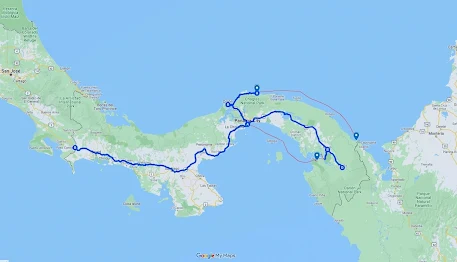

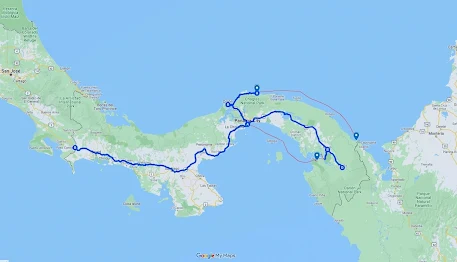

PANAMA

1081 Kilometres – 43 Days

18 April – 30 May 2012

17 April - Capurgana, Colombia – Puerto

Obaldia, Panama

It rained

hard during the night, causing a fresh and damp start to the day. The boat operating

between Capurgana, Colombia and Puerto Obaldia, Panama was expensive, and

waiting at the dock was best to get a better offer. Finally, a deal was made,

but the “regular boat” had a problem with the “good offer”. After fighting it

out amongst themselves, we were taken to Puerto Obaldia at no extra charge.

The

sea was rough, but our tiny boat got us safely to Puerto Obaldia where we proceeded

to the immigration office for a second time. Still, it took explaining in

broken Spanish (proudly presenting the embassy’s letter) that South Africans

didn’t need a visa to Panama beforehand. Nonetheless, we were told to return in

the morning when the boss was in the office. At least we weren’t sent back to

Columbia, like three days earlier.

The annual rainfall in the

area was more than 10m/a. Luckily, a covered area on the veranda of a derelict

community hall provided space to pitch the tents. By then, I had $85 to get

Ernest and myself to Colon, rumoured to be the first place with an ATM. Ten

dollars were spent buying food and a few beers and with rain gushing down, we settled

in. The roof we camped under at least allowed cooking and chatting.

Even though in Panama, we

weren’t out of the woods as no roads ran to or from Puerto Obaldia. The small

landing strip could nonetheless accommodate small planes. Still, I had no

money, and even if I did, the six-seaters which flew to and from Puerto Obaldia

couldn’t accommodate bicycles.

18 April - Puerto Obaldia

Following a long rigmarole,

Ernest and I were eventually stamped into Panama. Hallelujah!

Puerto Obaldia was a

military post with truly little happening. Meeting Simon, who hailed from Italy,

didn’t take long. Simon was travelling by 50cc motorbike from Ushuaia to Alaska.

He had, by then, already set a new record for distance travelled by a 50cc. For

several days, Simon had been stuck in Puerto Obaldia, searching for a boat

around the impenetrable Darien Gap. The Darien Gap is a break in the Pan

American Highway between Colombia and Panama. The area is a dense jungle

stretching almost 100 kilometres without roads or facilities. It’s considered

home to the lawless, anti-government guerrillas and drug-smuggling cartels. The

gap made overland travel across Central America pretty much impossible, and the

only way around was, thus, by sea or air.

Spotting a small wooden

cargo boat (the Rey Emmanuel) anchored in the bay, we searched for the captain,

who, like any good captain, was found drinking in the cantina. I didn’t know if

this was a good time to negotiate as I didn’t have enough money to pay for the

trip. Luckily, Captain Marseille was in a good mood

and offered us a fair price ($80 each) and agreed I could pay once in Miramar.

Furthermore, he informed me that

an ATM was located about 50 kilometres from where the boat was to anchor. The

trip was reportingly going to take between three and six days. Cooking wasn’t

allowed, and no food was included in the price. Armed with this information, the

three of us took off to the single shop to buy canned food, and ingredients we

thought one might be able to cook whenever the boat docked.

The only canned food at the little

shop consisted of spam and pork & beans, which we purchased, hoping one could

stock up at a few islands. The captain further informed us he could take us to

Miramar, a village along the Panama coast from where a road ran to Panama City.

The Rey Emmanuel delivered supplies to the San Blas Islands, a group of tiny

islands off the coast of Panama. The captain collected outstanding monies,

empty bottles, and gas cylinders on the return journey. I presumed the trip

would be a lengthy affair.

As the Rey Emmanuel was anchored

in the bay, a “lancha” had to be arranged to row us out to the boat the

following morning. According to the captain, he was departing at 9 a.m. sharp. Therefore,

not wanting to miss the only boat, a “lancha” was organised to ferry us across

at 6.30 a.m.

19

April – Day 1

The

following day, we gathered at the jetty eagerly awaiting our passage but were

told the captain was NOT leaving that day. Laughing at the madness, we hung

around and waited for further news. Nine o’clock came and went, and still we

waited, hoping something would crop up.

Then,

in a sudden rush of urgency, the captain emerged and told us he was sailing

that very minute. The two bicycles, motorbike, and luggage were hurriedly loaded

onto a “lancha” and paddled out with great urgency and speed. Besides the crew

on the boat were Simon, Matthias from Uruguay, a Colombian guy, and a lady from

Colombia on her way to visit family in Miramar. It has to be mentioned that the

boat was small and didn’t cater to passengers. The crew, therefore, wasn’t particularly

friendly, which one could understand as we were in their way. Finally, we all settled

down upon the wooden deck amongst the crates, trying our level best to roll out

mats to lie upon.

Eventually,

the boat sailed off; small and unstable, she rocked and rolled over the big

swells, while the three Europeans clung on, tooth and nail, not to be flung

overboard. Finally, there was little else to do but find a spot and wedge

yourself in, hugging your knees and feeling like a refugee. Moving around was

impossible, and due to the noise from the diesel engine, conversation was out of

the question.

After

roughly three hours of sailing, we caught our first glimpse of the San Blas Islands.

Three hundred and sixty-six islands, and a few so tiny they could barely

accommodate one or two huts. Once amongst the islands, the sailing was far

smoother. Still, it remained impossible to move about or chat. The captain anchored

twice to pick up empty gas cylinders and empty crates of cooldrink bottles.

Finally,

Captain Marseille must’ve relented about the meals as all passengers were served

lunch (rice accompanied by chicken wings and feet, give me strength!). By 4 p.m.,

the Rey Emmanuel reached yet another tiny island, where she moored for the

night. Supper consisted of cooked bananas (plantain), cassava and salted pork

or, -, pork fat.

Three

other boats also moored along the jetty, and everyone knew one another. Soon darkness

fell, and all settled in, crew in hammocks and passengers underneath them on the

hard, wooden slats of the boat deck.

20

April – Day 2

Our

first morning dawned, and the boat sailed out of the small harbour at around 6

a.m. The first stop was shortly afterwards at an island village to collect the

necessary goods, where a breakfast of boiled banana and chicken feet was

served.

As

a vegetarian I had great difficulty with the food. Still, the others were happy,

as there was a lack of shops on the islands. The cans of pork & beans

purchased turned out simply beans in watery tomato juice – quite gross. Gross

or not, we had quite a few of these cans to work through, and I had a choice

between chicken feet or beans in a watery tomato juice. Soon after departing,

the crew caught a large fish, and I was sure it would be our evening meal.

The

inhabited islands were packed “wall-to-wall” with reed and palm-thatch shacks.

Islanders wore traditional clothes and were surprisingly short. The Rey Emanuel

slowly putt-putted between the San Blas’ teeny islands, stopping numerous times

to load empty crates and gas cylinders, and collect outstanding money. The Rey

Emmanuel couldn’t have covered much distance before our overnight stop. Sure

thing – supper consisted of rice and fried fish, which was a great deal more

edible than the salted pork fat.

Life

in the San Blas was at an unhurried pace. With no electricity, we all went to

bed when it became dark and woke at sunrise, making it a long night on the

uncomfortable deck.

21

April – Day 3

Day

3 brought an earlier departure than the previous day. Breakfast was served at

the first island stop, consisting of boiled banana and salty pork fat. I’m not

ungrateful, but I couldn’t eat it. The crew, on the other hand, seemed

delighted with their breakfast. Mercifully, we still had a few stale rolls,

half a jar of peanut butter, and the famous pork & beans (without pork).

Following

loading, sailing continued past numerous small islands with coconut palms and

white, sandy beaches. They looked idyllic, and the water was clear enough to see

fish swimming even in the deeper water – the San Blas was indeed close to

paradise. Unfortunately, the Kuna people were shy and didn’t like being

photographed. I did, nevertheless, manage to steal a blurry shot or two. Small bare-bum

kids ran about or rowed their wooden dugout canoes, seemingly before they could

even walk.

The

days became increasingly hot, but it wasn’t too unbearable while sailing.

Still, the heat sent everyone running to a shady spot when we moored. The

rhythm of loading, off-loading, and then sailing to the next island to do the

same became a familiar routine. While we moored, food was served, and a good

thing too, as the boat rocked far too severely to cook or eat. Lunch was rice,

beans and liver. I happily gave my liver to Ernest and ate the rice and beans,

neither of which would ever make it to my favourite list.

By

evening, anchoring was at a relatively large island, for the San Blas, (approximately

500 metres x 800 metres). We all sat watching the teams play basketball and I

thought it a good thing the tiny Kuna people played each other. Supper

consisted of a boiled banana and fried fish. We sat around the square until we

realised this was it, and nothing more would happen. Then, when darkness fell, we

all crawled in, trying to get as comfortable as possible while listening to the

snoring and farting of the crew in their hammocks above.

22

April – Day 4

The

Rey Emmanuel stayed moored the entire day as the captain had business to attend

to. Still, I never saw him doing anything but swing in his hammock, or drink

beer on the dock. At least breakfast was slightly different, and consisted of

boiled banana and tinned meat (spam). The island sported a branch of the Bank

of Panama and someone mentioned an ATM inside and we decided to check it out in

the morning.

So

small was the island that it took no time to criss-cross it. It rained on and

off for the greatest part of the day and the kids loved it, playing endlessly

in the puddles and never seeming to tire. Each island had a central basketball

court where all gathered. The courts were well-used, and various basketball and

football games were played simultaneously. I felt privileged to have the

opportunity to experience these remote islands.

23

April – Day 5

The

following day, we were up early to be at the bank as soon as the doors opened,

but after rushing over in the bucketing rain, we found no ATM inside. Receiving

wrong information seemed a daily occurrence. Tails between our legs and

empty-handed, we returned to the boat to eat our fish and boiled banana

breakfast.

Instead

of sailing in the morning as planned, nothing happened, and we all sat around

waiting. The rain never ceased and could’ve been the reason for a non-sailing day.

Lunch was crab and rice, and everyone was delighted except me.

Captain

Marseille finally steered us off to the next island at around 3 p.m. The boat putt-putted

through the islands for roughly two-and-a-half hours before anchoring. Supper

was rice with tinned sardines, and we were all grateful for the change of

cuisine. Still, we fantasised about pizzas, wine, coffee, and whatever people

could think about.

Unfortunately,

the weather turned absolutely foul, with a strong wind and bucketing rain. The

boat rocked and rolled, and the crew swung wildly in their hammocks (some

eventually opted to sleep on the floor). Simon tried sleeping on the dock, but

the rain soon drove him back onto the boat.

24

April – Arriving in Miramar – Day 6

With

the rolled-down canvas (to keep the rain out), we all slept late, and it must’ve

been around 7 a.m. before our unfriendly crew started moving about. The boat was

out of coffee for days by then, but they must’ve found a wee bit stashed away

somewhere as there was a sip of coffee before breakfast. Then, in a sudden

spurt of urgency, the engines were started, and in no time the boat was untied

from the quay, nearly leaving Matthias and the Colombian guy who had camped

ashore behind.

The

sailing routine continued to the next island, where the captain collected

outstanding money and served breakfast. Rumour had it this was our last stop

before a straight six-hour sail to Miramar. We all had enough of the boat by

then and couldn’t wait for the trip to be over.

Immediately

after clearing the San Blas islands and reaching the open ocean, the weather deteriorated. I am not speaking hyperbolically

when saying I feared our tiny boat wouldn’t make the final stretch. She rolled

and pitched, and whatever wasn’t latched down, came flying across the deck. It

was a scary experience, and landing at the bottom of the ocean was a real

possibility. There was little to do but wedge yourself in between the cargo and

hope for the best. The rain came down so hard that the engine noise was virtually

drowned out, and visibility was barely a few metres.

Finally,

and to everyone’s relief, the Rey Emmanuel, against all expectations, docked in

Miramar in the late afternoon. We couldn’t have been happier being off the

boat. All the passengers went in search of accommodation in the village. Ernest

and I shared a room, and Simon, Matthias and the Colombian guy were in the

other room. The place was pretty basic, but I think we were all happy to be on

a mattress of sorts and to shower (the first in more than a week).

By

this time, no one had any money and Ernest cooked our leftover pasta mixed with

the infamous pork & beans without the pork. Matthias also threw in his last

few cans and, in the end, it became quite a substantial pot of food.

25

April - Miramar – Portobello – 44 Kilometres

Early

morning, I gave Ernest my bank card and Simon gave him a lift on his 50cc

motorbike to the ATM at Portobello, almost 45 kilometres away. I still had to

pay for the boat trip and the captain had kept my bicycle on the boat as ransom.

I also had to refund Matthias as he kindly paid for the previous night’s

accommodation.

This

was all easier said than done as the motorbike’s front tyre had a large hole,

and Simon glued a piece of old inner tube over it. I had my doubts as to

whether the tyre would last 45 kilometres. Soon after their departure, the

Colombian guy hurriedly caught a bus to Panama City. Matthias and I waited until

Simon and Ernest returned.

They

returned all smiles, and although Simon hadn’t been able to get any money in Portobello,

at least I had money to pay for the trip, and could get my bike out of the

pound. Unfortunately, Simon discovered that his costly Canon camera and lens

had vanished from their room. He straightaway reported the incident to the

police, but they could do little.

Eventually,

Ernest and I saddled up and headed along a lush and forested route toward Portobello.

The way was reasonably good but came with a few steep hills. Still, we reached Portobello

in good time. I was pretty surprised to find a tiny, but fascinating, village sporting

the remains of an old castle and fort.

Many

international sailing yachts anchored in the bay - indicating this was a

popular sailing route. The well-known Captain Jacks was a tad pricy for a dorm

bed, and looking elsewhere was best. In the process, we located the reasonably

priced Hospedaje La Aduana. While not the cleanest, and with mice nibbling at

our food bags during the night, the place wasn’t all bad as the room featured a

large balcony from where to people-watch.

26-27

April - Portobello - Colon - 44 Kilometres

I

awoke with an upset stomach and felt like I had dined from a garbage truck the

previous night. Despite this, we packed up and biked along a scenic coastal route

to Colon.

Unfortunately,

my camera was playing up and, as Colon was a free trade zone, we turned in to

see if there were any camera bargains. There were plenty of warnings about Colon

being a nasty and dangerous place. We, nonetheless, met only friendly people

(all warning us about the dangers), ready to help us find a safe place to

overnight. Our hotel was lovely, and I searched out the free trade zone. Unfortunately,

I thought the shops were a rip-off, not a place to get a good deal. I looked

but couldn’t see any cameras I liked at a reasonable price and thought it best to

have mine fixed.

The

following day was laundry day and time to sort out internet tasks, which was

long overdue by then. Colon was close to the Panama Canal, but I never saw the

canal.

28-30

April - Colon – Panama City - 90 Kilometres

Panama

is a small country that made for effortless pedalling across from the Atlantic

coast to Panama City on the Pacific coast. The ride wasn’t bad; a tad hilly but

no rain. On riding into Panama City, we encountered a sprawling, cosmopolitan area.

The city was the centre for international banking and trade in Panama and, hence,

sported a modern skyline of glass and steel towers.

Biking

around searching for a budget room revealed we were in the wrong area. Instead

of budget accommodation, we only found international hotels to the likes of Le

Meridian, The Radisson and the Continental. Ultimately, a more reasonably

priced room was discovered in the old part of town.

The

next morning, an even less expensive abode was sought and, in the process, we rode

through the old town and onto the famous Panama Canal. Panama City was situated

at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal. Still, the canal wasn’t half as

impressive as the Suez Canal, and I thought it was an audacity to charge an

entrance fee.

In

Panama, sunrise was at approximately 6:20 a.m. and sunset at around 6:20 p.m.,

every day, year-round—no wonder it’s amongst the world’s top five places to

retire.

Sadly,

my camera packed up entirely, and I searched for a new one or a place to fix it.

Being Sunday, I found the majority of shops closed. The next day turned out a

public holiday, and little got done.

1-2

May - Panama City

Back

and forth between all the large shopping centres I went. Firstly, in search of

a place to fix the camera and, secondly, to check on new ones’ prices. Both

were found and I handed my camera in to be repaired, but then went wild and

bought a new Canon Rebel. This deed, unknowingly, marked the start of a long

love affair with Canon.

I

spotted a professional-looking bike shop, handed the bicycle in for a service,

and then returned to the room to play with my new toy.

2

May - Panama City

The

old town, known as Casco Viejo, had a fascinating history. The city was a

significant trading post for oriental silks and spices. Being a wealthy city, Casco

Viejo was the envy of many pirates. In 1671, the town was ransacked and

destroyed by the Welsh pirate, Sir Henry Morgan, leaving only the stone ruins

of Panama Viejo. At the time, the area consisted of crumbling buildings and

narrow lanes, forming part of a high-density slum. Even though the suburb was considered

unsafe, the only danger we encountered was the missing drain covers.

3-4

May - Panama City

Panama

was a confusing country, direction wise. Due to its ‘S’ shape, north, south, east

and west were never where I expected. In Panama City, the sun rises over the

Pacific Ocean and sets over the Atlantic Ocean. It surely must be the only

place in the world where that happens. The canal, therefore, runs roughly north

to south (not east to west, as imagined). Weird.

5

May - Panama City – Chepo – 73 Kilometres

The

camera repairs would take 20 days and I was secretly happy as this allowed

heading into the Darien. Unfortunately, the unsurpassable jungle of the

Panamanian Darien Region had a reputation for danger (drug traffickers and

Columbian rebels). Still, my desire to explore was mainly due to the area being

one of the most remote places on Earth.

I

was excited to get going, but Ernest dragged his heels, (big eye-roll) and the

time was 11 a.m. before we finally got underway. As a result, nearly the entire

way was built up, and it took almost 50 kilometres of cycling before the road

spat us out in the countryside.

On

arrival in Chepo, we met Mr Singh, who ran the Pizza King. Chatting with him, we

learned he had lived in South Africa for almost five years. No sooner were the

panniers off-loaded than Mr Singh presented us with a pizza. He further

insisted we visit the shop for coffee and cake. That evening, an enjoyable time

was spent chatting about his life in our home country.

6

May - Chepo – Unknown settlement – 60 Kilometres

Woken

by Mr Singh, who invited us to breakfast, didn’t come as a surprise. After

scurrying across the road, we had a good old chat while enjoying his

complimentary breakfast.

No

sooner had we departed than it started bucketing down, forcing us to take shelter

until the worst had passed. To our surprise, the paved section ended abruptly, and

the ride became a battle along a muddy, gravelly path until, finally, a paved

road reappeared.

Finally,

at around 5 p.m., we reached a settlement where pitching the tents was at a cantina.

I can assure you no cantina has ever made peaceful camping. The music blared

until late in the evening and people were understandably noisy. I could only

hope no one would fall on the tent. Covered in mud, but with no privacy to

wash, I crawled in, muddy feet and all, humming ‘There are days like this’.

7

May – Unknown settlement - Torti – 38 Kilometres

One

went through stages of things breaking. This must’ve been the tent-pole-breaking

stage, as in one night, both Ernest and I suffered broken tent poles. Luckily,

duct tape, cable ties and the odd hacksaw blade came in handy. Following a late

start, the route led past unmapped hamlets featuring thatched huts and

indigenous people going about their daily tasks. I, however, found the amount

of deforestation in the area alarming.

Upon

arriving at Torti, Ernest spotted a hotel. The price was reasonable, and I desperately

needed a shower and booked in. The room came with hot water, which made it an

excellent opportunity to do laundry. Torti was an area where farmers still

travelled by horseback, hence it was the place to find the iconic saddle makers,

who made magnificent, decorative saddles.

8

May - Torti – Meteti – 77 Kilometres

On

entering the Darien province, the path deteriorated even further. Nevertheless,

the ride was picturesque through a densely forested area. Police stops were frequent,

and bags were searched. Precisely what they were after, I couldn’t figure out.

Drugs, I guessed.

Once

again, I couldn’t believe ants bit me, and it appeared I had developed a slight

reaction to ant bites. I immediately started itching under my armpits. It seemed

worse every time it happened. How strange.

Luckily,

we reached Meteti early and shortly before the rain came down. It rained so hard

we could barely hear each other, just the weather one could expect from one of

the last remaining wildernesses.

9

May - Meteti – Yaviza – 54 Kilometres

The

weather wasn’t merely sweltering but also exceptionally humid. Like any good

jungle road, the area had a few hills. At Yaviza, our route came to a grinding

halt. The village marked the end of the Pan-American Highway and the start of

the infamous Darien Gap. The assumption that there would be a boat from Yavisa to

La Palma was clearly incorrect. This meant we had to backtrack to Puerto Quimba,

where we were told boats left for La Palma. The lack of information made this

more guesswork than anything else.

10

May - Yaviza – Meteti – 55 Kilometres

Backtracking

wasn’t all terrible as we escaped the rain and it became a pleasant day of

cycling. A vendor presented us with pineapples, avocados, mangoes, and a

strange unknown fruit. He wanted no money, and with panniers bulging, we continued

until Meteti.

11

May - Meteti – La Palma via Puerto Quimba – 20 Kilometres

Departing

Meteti was at a leisurely pace to cycle the short distance on a slightly hilly

and gravelly road to Puerto Quimba. The area was beautiful in its remoteness and

at times so quiet that the forest noises sounded deafening. Once in Puerto

Quimba, a boat to La Palma was located and, being a short distance, the ride barely

took 30 minutes.

La

Palma, capital of the Darien Province, strangely, wasn’t reachable by road and

consisted of a few colourful houses on stilts. La Palma only had one ‘street’

along a muddy riverfront. There was nothing else besides the few shops, bars,

and restaurants lining the only path. Our accommodation consisted of a ramshackle

stilted bungalow where one couldn’t just hear the water sloshing underneath but

could also see it through the floorboards.

12

May - La Palma – Sambu - By boat

Initial

information was that the boat to Sambu was in two days. Still, at the slipway, one

got the impression there could be a boat that very day. Someone once said the

service in Sambu was “as slow as molasses” and I couldn’t think of a better

description. There was little else to do but hang around, watching boats come

and go.

Eventually,

a boat appeared, and we flew across the Gulf de San Miguel at breakneck speed

on an open speedboat. At the same time, brown pelicans and shearwaters drifted

effortlessly above. The Gulf was scenic and peppered with tiny islands.

Soon

after setting out, the boat turned up the River Sambu and, after two hours,

arrived at the little settlement of Sambu, home to the Embera and Cimarrones.

Interestingly enough, these were people of African descent whose ancestors

escaped the slave trade by living in the jungle. Sambu was situated deep in the

forest, and one would never have spotted it without getting off the boat.

Albeit

tiny, the settlement was considered substantial for the Darien as it had a

payphone, landing strip, clinic and school. The centre of the village was a

large, shady mango tree where everyone gathered. If wanting to contact anyone

in the community by phone, the payphone was the number to dial, and anyone in

the vicinity of the phone would answer.

The

landing strip was the single paved road in the area, and where kids rode their

bikes and lovers took a stroll in the evening. Ernest and I overlooked the

action from our little veranda, and I was pretty happy being there. Watching

the activities, I realised that although the Embera people lived in reed huts

on high stilts, cooked on open fires and wore traditional clothes, they were no

different from city folk.

13

May - Sambu

Early

morning, I sauntered to the river where people bathed and I watched village

folk go about their daily tasks. We later inquired about a boat to Panama City.

The answer was, yes, there was indeed one, maybe today, maybe tomorrow.

When

the boat finally arrived, I was pretty shocked at the state of the old rust

bucket. It didn’t appear seaworthy or capable of reaching the capital. I was further

slightly concerned about getting myself, panniers and bicycle up the narrow gangplank

and onto the deck. Word had it the Doña-Dora was sailing the following morning.

The reason for the delayed departure soon became apparent. The tide went out

leaving the Doña-Dora firmly on the muddy riverbed. At least we knew she wasn’t

sailing without us.

My

trundling resulted in an invitation into one of the homes. I was surprised at

how spacious and airy these homes were, and interesting to see they cooked on

open wood fires even inside. A concrete slab was placed in one corner for this

very purpose.

I

bought a wrap-around skirt from the lady and felt I blended in a little better

(ha-ha, not that I would ever blend in at all). As there were no shops, vendors

pushing wheelbarrows appeared, selling their wares. Fish, cucumbers, even a cow’s

head, and later the shrimp man, whom Ernest supported. He must’ve overeaten as he

was dreadfully sick during the night. By evening, I sat on the balcony,

watching a lightning display and listening to the sounds of the forest.

14

May - Sambu

We

were operating in low gear and when told the boat was only departing at 10 p.m.,

the news was taken in our stride. Unfortunately, it rained the best part of the

day, and there was little else to do but watch the Embera people paddle their

dugout canoes.

Each

household had a few chickens which were, by far, the ugliest chickens. Fish were

the staple diet as riverside living made easy fishing, even if just catfish.

Rice, beans, bananas, mangoes and avocados accompanied all meals.

By

late afternoon, we headed to the Doña-Dora where it required a trapeze artist’s

skills to get our stuff and ourselves onto the boat, as the sole access was via

a long and narrow gangplank. Once on the boat, we found tiny wooden cabins – six

bunks to a cabin, leaving little headroom or manoeuvring space. Most bunks were

broken and not all the beds could be used. Our fellow passengers were quite interesting,

travelling with live lizards in hessian bags, parrots in boxes and buckets of

fresh seafood. I’m not kidding you!

15

May - Sambu – Panama City - By boat

The

following day, the boat anchored in the Gulf, off the village of Geruchine,

where launches came out to meet us. Plenty of fish, empty drink crates, gas

cylinders and more passengers were loaded. Getting on board was quite a

spectacle as passengers had to be pushed and shoved onto the Doña-Dora from the

panga boats which came alongside.

Once

out of the Gulf de San Miguel, and in the open waters of the Pacific Ocean, we sailed

along smoothly while watching dolphins and flying fish. Seeing flying fish was

a novelty and this wasn’t even the South China Sea, where the flying fishes

played according to Kipling. Brown pelicans followed in our wake, diving for

food, while shearwaters soared above.

The

meals served were based on boiled bananas and their staple of rice and beans. Although

not haute cuisine, the cook was a great deal better than on the Rey Emmanuel (at

least it wasn’t just chicken feet and salted pork fat).

At

around midnight, we cruised into Panama Bay. Coming from the jungle, the night

view of the towering city lights was quite spectacular.

16-19

May - Panama City

I

woke on our rocking boat and could barely believe the Doña-Dora had made it to

Panama City. We watched the city skyline, waiting for high tide to go onto the

pier. Breakfast and lunch were served, and as other passengers had gradually

left by small launches, the meals served were heaps better.

The

high tide allowed for mooring, but the swell made getting bikes and panniers

off the boat tricky as the boat bashed back and forth against the dock.

However, I was more than ready to get off and be on my way. Once off the boat,

we headed to a hotel to shower. A nearby supermarket provided supper, which was

much different from the past few days.

20

May - Panama City – Capira – 55 Kilometres

Departing

Panama City meant biking across the Bridge of the Americas, which spanned the

Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal. There was no riding over this bridge

without snapping a few pics of the container ships coming into the canal.

The

rest of the day was spent biking along an excellent but hilly route as we

followed our noses toward Costa Rica. As usual, the day came with blistering

heat and high humidity, which required frequent stops to fill up with water.

Upon

reaching Capira, a rural settlement in the Cermeno Mountains, we found a

typical Spanish Colonial-type town centred around a church plaza. A room with a

balcony, where I could watch the rolling hills around the city, was home that

night.

21

May - Capira – Anton – 79 Kilometres

The

next morning, we returned to the Pan-American Highway, which was pretty much the

only way to Costa Rica. Meeting other cyclists, thus, didn’t come as a surprise

as it was very much the classic North-South bicycle route. The last time biking

this highway was in Chili, many moons ago. No highway ever made exciting riding

and it became a monotonous and uneventful day.

22

May - Anton – Aguadulce – 73 Kilometres

Early

morning, a truck driver stopped and offered me a cycling helmet. He told us the

highway was dangerous with many trucks and it was safer to wear a helmet. What

a thoughtful man. Again, we met other cyclists heading to Panama City, which

was the end of their journey. The road flattened out, making it comfortable riding.

The rain we encountered soon cleared, and we made our way to Aguadulce.

23

May - Aguadulce – Santiago – 58 Kilometres

Central

Panama, situated between the continental divide and the Pacific, was a sparsely

populated area, dotted with farms and ranches. I watched in fascination how ranchers

herded cattle by horseback, which is always a pleasure to observe.

Using

a public phone confirmed my camera would be ready the next day and we stayed

put.

24-25

May – Santiago

Early

morning, I caught the bus to Panama City, picked up the camera and jumped on a

bus for the return trip to Santiago. This little excursion was a whole day

affair and arriving in Santiago was after dark. At least I had my old, trusted

Panasonic back.

26

May - Santiago – Los Ruices – 64 Kilometres

The

day’s riding was considerably more demanding than anticipated with the weather

sweltering, humid and hilly. The going was slow, and all I saw was the sweat

from my face dripping on the tarmac. So hot was it, by mid-day, I felt faint

and nauseous, but there was little one could do but soldier on.

By

afternoon, a teeny settlement with an abandoned restaurant and small veranda made

it good enough spot to pitch the tents. Discovering a laundry trough with

running water out back was a bonus. Ernest cooked pasta and, as there was

little to do when wild camping, we crawled in early.

27

May - Los Ruices - San Feliz – 58 Kilometres

On

packing up, Ernest discovered a broken spoke and nothing came of our planned

early start. It seemed there was no escaping the heat and I keenly looked at

the sky wishing for a cooling shower. Regrettably, it became one more rainless

day.

Mercifully,

the route reached a high point, and the remainder of the day was a beautiful

ride through the mountains, where the highlight was encountering the Guaymi

tribe. Guaymi women made traditional crafts for their own use and to sell for

extra income. These included handmade bags from plant fibres called “kra,” colourful

dresses called “nagua” and beaded bracelets and necklaces. Men, typically, made

hats from the same material.

When

the Spanish arrived in Panama, they found three distinct Guaymi tribes in what

is today western Panama. Each was named after its chief, and each spoke a

different language. The chiefs were Nata, Parita and Urraca. Urraca became

famous as he defeated the Spaniards, forcing them to sign a peace treaty in 1522.

Nonetheless, Urraca was betrayed and captured, but escaped and made his way to

the mountains, vowing to fight the Spaniards unto death, a vow he fulfilled. The

Spaniards feared Urraca so they avoided combat with his men. When Urraca died

in 1531, he was still a free man.

Several

Guaymi still choose to live secluded lives away from modern society and with few

facilities.

28-29

May - San Felix – David – 84 Kilometres

The

day was marred by blistering heat. Fortunately, there weren’t any hills, but the

road deteriorated, and the shoulder vanished altogether. The heat made riding

exhausting, and I was dead tired getting to David.

Parque

Cervantes was surrounded by vendors selling anything from clothing to fruit

juices (mainly lottery tickets). Accommodation was a pricy affair, but I couldn’t

care less as I only wanted to shower and lay down. We stayed an additional day to

do the dreaded laundry.

30

May - David, Panama – Paso Canoas, Costa Rica – 55 Kilometres

Following

a leisurely departure, we found the route levelled out, making it comfortable riding,

past plenty of fruit sellers en route to the Panama-Costa Rica border. The

border crossing was an uncomplicated affair, which simply required a stamp in

the passport.

Plenty

of duty-free shops lined the road and after searching for bargains, none were found.

Being a typical border town, Paso Canoas was packed with trucks and buses, dodgy-looking

money changers and food vendors. Still, Ernest wanted to stay and continue in

the morning. He had his reasons.